Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru

At a Glance

- Size: 9.5 ha (23.5 ac)

- Variety: Chardonnay

- Vine Age: Planted from 1949-2007; 50 years average vine age in 2016

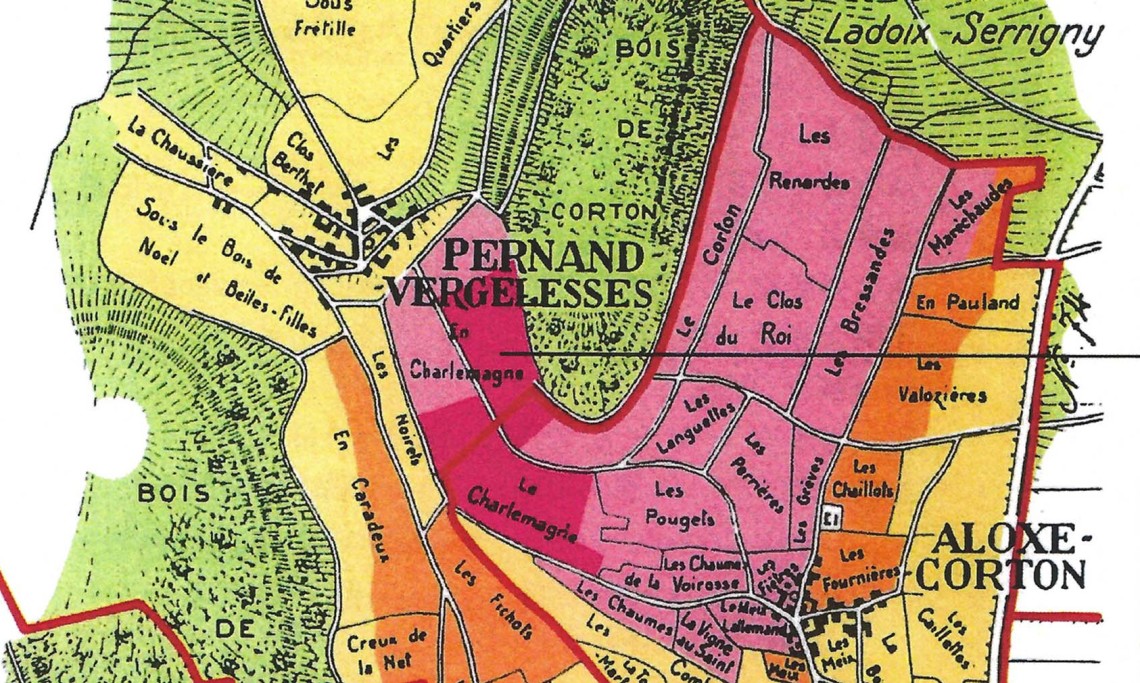

- Terroir: 15 contiguous parcels facing west in En Charlemagne and Le Charlemagne. There is almost no clay in the topsoil which is made of silt and sand, it lays over white marl. Up to 30% slope.

- Viticulture: Certified organic (Ecocert) biodynamic

- Vinification: Indigenous yeast fermentation. Lees-stirring as needed. Aged initially in oak barrels (30% new), fining to tank with fine lees over winter.

Additional Info

Since 2008, when the composition of Romanée-Conti’s cuvée Duvault-Blochet changed to include 1er crus, Bonneau du Matray has been the only domaine in Burgundy to produce only grand cru.

Bonneau du Martray owns 11 hectares of grand cru on the hill of Corton, making it the largest owner of any single grand cru. 9 ½ hectares are planted to Chardonnay, 1 ½ is planted to Pinot Noir. The proportion planted to Pinot used to be larger, approximately 2 ½ hectares. His father almost ripped it all up but Jean-Charles dared him to keep some, telling him “you want to uproot the Pinot because you don’t know how to make red wine.” Up to the mid-seventies, 1 hectare was still planted to Aligoté. A few bottles of it remain. They are rumored to be brilliant.

The Corton-Charlemagne is divided into 15 parcels, all of which are vinified and aged separately, until the second racking. When Jean-Charles took over the domaine about ¾ of it was planted to selections massales. The clones his parents used to replant were very good ones. But wanting to preserve the mutations specific to his vineyards, he has his own conservatory. For now, he still uses both clones and massales for vine replacements.

The domaine’s land is contiguous and is situated in the heart of the appellation, in En Charlemagne in Pernand-Vergelesses, and in Le Charlemagne in Aloxe-Corton. It most likely includes the 1.5 hectares owned by Emperor Charlemagne until 775. The vineyards are located on a diagonal that runs from the top En Charlemagne to the bottom of Le Charlemagne.

An oddity in Cote d’Or, the vineyard faces west —west/southwest in Aloxe, to west/northwest in Pernand. It is the only grand cru in Cote d’Or exposed to the setting sun and it gets substantially longer sunlight in the evening than the east facing slopes. Vines functioning through photosynthesis, Jean-Charles believes that this unique exposition is the main reason why Corton-Charlemagne stands apart from the other white grand crus, displaying extraordinary intensity, yet with little fat.

In 2006, Jean-Charles commissioned a geological study of his domaine. It revealed 9 distinct geological facies. In general, Corton-Charlemagne has almost no clay. Its topsoil is mostly silt that contains a lot of silica. It sits on a bed of white marl. Depending on where you are on the hill, the blocks of rock dip in opposite directions: down at the bottom of the slope, up at the top. There is a zone of faults in mid-slope. The sandy nature of the topsoil is a worry, and highly subject to erosion. The hill is steep for Burgundy, up to a 30% grade.

The west facing slope sits at the mouth of the valley of Echevronne, where Jean-Charles says there is a quasi-permanent breeze. Even when everything appears to be totally still, the direction of the biodynamic sprays leaves no doubt that there is air movement.

The Hill of Corton: Myths, Truths, Maybes

1. Charlemagne owned the land on the hill of Corton: VERY LIKELY

In the 8th century, France was not yet France but a collection of Frankish kingdoms ruled by the last kings of the Merovingian dynasty. That they were the last ought not to have surprised even them since they were known as les rois fainénants, the lazy kings, kings in title only who left the ruling of their kingdoms to their mayors of the palace, a sort of omnipotent prime minister.

During the second decade of the 8th century, Charles Martel, Charlemagne’s grandfather, rose to the title of mayor of the palace and de facto ruler of the Franks by strong-arming the Frankish kingdoms into unity. At that time the southern Frankish territories from Aquitaine to the Loire Valley were under siege by the Saracens who had already conquered the near totality of the Iberian Peninsula. Charles who was a brilliant military leader crushed the Saracens in 732 at Tours. After Tours, persuaded that the Burgundians had not valiantly enough opposed the Saracen armies (and that some had even collaborated with the enemy) Charles reorganized Burgundy and confiscated several ecclesiastical properties possibly land or vineyards on the hill of Corton[1] and that they were eventually passed down to his grandson Charlemagne.

But in 775, Charlemagne bequeathed them to the monks of Saint Andoche in Saulieu, in compensation for the destruction of the Abbey by the Saracens[2]. Though Charlemagne’s donation act is believed to have been destroyed in a fire in 1360, some inhabitants of Aloxe-Corton claim to have seen it at a later date [3]. The first documentation of the Clos dates of 1375, it mentions surface of 36 ouvrées (1.5 ha).

Incidentally we know that Charlemagne also owned vineyards in the Loire, Lorraine, Alsace, and the Rheingau, and that he was a bon vivant, that he loved to drink and eat. From the Capitulare Devillis, a set of the rules to be observed in the management of his estates, we know he paid close attention to the vineyards: “That our intendants take charge of our vineyards and that they take good care of them, that they place the wine in sound containers and make sure that it doesn’t spoil in any way. Furthermore, that they purchase wine from the trade in order to furnish the royal estates; and if it happens that too large a quantity of wine was purchased than was necessary, that it may be brought to our knowledge so we may let our will known on the matter. That they make arrangements to send for our own use the produce from the vines of our vineyards. That they send to our cellars the product from the tax on our estates that must produce wine.”

1. Claude Chapuis, Aloxe Corton; 2. Courtépée, Description Historique et Topographique du Duché de Bourgogne; 3. Chapuis, p.15.

2. Charlemagne orders the plantation of the hill of Corton: MYTH.

Noticing that the snows always melted first on the hill of Corton, Charlemagne ordered it to be planted to vines. The same story is also told about Schloss Johannisberg in the Rheingau. However the first references to vineyards in Aloxe dates back to 696[1], and because the flatlands in Aloxe were marshes[2], it appears logical that it was the hill that was planted even then.

1. & 2. Jancis Robinson, Oxford Companion to Wine

3. Tired of the red wine stains on Charlemagne’s great white beard, his wife Luitgarde orders the Emperor’s vineyard planted to white rather than red: MYTH.

At 6 feet 4 inches, Charlemagne was unusually tall for the times and towered over his subjects. He “had a round head, large and lively eyes, a slightly larger nose than usual, white but still attractive hair, a bright and cheerful expression, a short and fat neck” [1]. He is immortalized in France as l’empereur à la barbe fleurie, the emperor with the flowery beard, because of his purported great Santa Claus-like white beard. He was an all around bon vivant, who loved to eat and drink well and “he enjoyed good health, except for the fevers that affected him in the last few years of his life. Toward the end he dragged one leg. Even then, he stubbornly did what he wanted and refused to listen to doctors, indeed he detested them, because they wanted to persuade him to stop eating roast meat, as was his wont, and to be content with boiled meat.” [2]

Charlemagne’s last wife, by some accounts his fourth, by others his fifth, was Luitgarde, a beautiful German princess, who was described by one of her contemporaries as “admirable in appearance, but even more admirable in her behavior and morals, generous, affable and charitable, as spiritual as she was beautiful, she loved the arts, and worked to embellish her spirit.”[3] Emperor Charlemagne is said to have adored her, and though she died very young, he never remarried.

“As Charlemagne grew older, and his beard whiter, his wife Luitgarde, ever watchful over the dignity of her spouse, objected to the majesty of her emperor being degraded by red wine stains on his beard and suggested that he switched to consuming white wine. White grapes were commanded to be planted on a section of the hill, Corton-Charlemagne was born, and it continues still.” [4]

This lovely story is highly unlikely. Charlemagne and Luitgarde were married in 794, and as we have seen, in 775 Charlemagne had bequeathed his Corton vineyards to the church. Others believe that it was Charlemagne’s mother, Bertrada de Laon, otherwise known as Bertrada Broadfoot, who was offended by the stains on her son’s beard and convinced him to change the vineyard over to white.[5] Unfortunately, this interpretation fails to deal with the most serious blow to the theory of the beard, for historians agree near unanimously that Charlemagne was not l’empereur à la barbe fleurie, but instead, that he had no barbe at all. It was simply customary later in the middle ages to depict rulers with facial hair, even if they had none, to underline their virility.

1 & 2. Einhard, Vita Karoli Magni; 3. Mrs. Forbes Bush, Memoirs of the Queens of France; 4. Clive Coates, Côte d’Or; 5. Chapuis

4. Charlemagne replants his Corton vineyard to white for diplomatic gain: MAYBE.

According to Corrine Lefort [1] Charlemagne had initiated contacts with king Offa of Mercia who ruled over a powerful Saxon kingdom and who preferred white wine. Offa wanted to exchange Charlemagne’s white wine for wool. To satisfy Offa, the parcels at the top of the hill of Corton were replanted to white. Corinne Lefort mentions the following bibliography: Charlemagne et l’Empire Carolingien by Louis Halphen, and Charlemagne by Georges Tessier. Wikipedia in its article on Offa of Mercia, points to Stenton, Anglo Saxon England, pp. 215, 220.

1. Corinne Lefort & Karine Valentin, Grands Palais: 2500 ans de passion du vin; and Corinne Lefort, Charlemagne (742-814) Sous l’empire des vins de Corton, Revue du Vin de France, Juillet.Aout 2004

5. There was white on the hill of Corton, but Latour was the first plant Chardonnay: MYTH

Most authors, including Clive Coats and Matt Kramer, downplay the reputation of white Corton or Corton-Charlemagne prior to the apparition of Chardonnay in the vineyard. Here is Matt Kramer: “The real history of this extraordinary vineyard only begins when Corton-Charlemagne allied itself to Chardonnay. You would think that had happened almost from the start. Instead, it is traced only to the late 1800s when the great-grandfather of the current Louis Latour replanted part of his holdings in Corton-Charlemagne to chardonnay. This was revolutionary. Prior to this break with tradition, the wine of Corton-Charlemagne came from three grapes: Aligoté, Pinot Blanc, or Pinot Gris (called Pinot Beurot). (…) This recent conversion to Chardonnay helps explain why Corton-Charlemagne is not counted among the greatest white Burgundies by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers. Rather, it was various Meursaults and, above all, Montrachets, that garnered the huzzahs.”

First of all, in 1855, if Lavalle does not delve with great detail into the whites of the hill of Corton, he does places them on a par with Bâtard-Montrachet and Meursault-Perrières, just below the supreme Montrachet. And prior to that, Courtépée, in 1778, states: “Excellent climat called Corton, from the name of a neighboring wood. Once a famous white wine, destroyed since one has been made aware of the quality of the red.”

Secondly, as to chardonnay only appearing in Corton-Charlemagne in the nineteenth century, this is a misinterpretation of nineteenth century authors who were writing at a time before chardonnay had been clearly identified and was still mistaken for pinot blanc. When Lavalle writes that Aloxe is planted to pinot noir, pinot blanc, and pinot gris, one should not take pinot blanc literally. The differentiation between Chardonnay and Pinot Blanc was only firmly established in the late 19th century. What Lavalle and others mentioned as Pinot Blanc, was in fact almost certainly Chardonnay.

From Durand & Guicherd, in 1896:

“Pinot Blanc: M. Pulliat mentions this varietal known as a white type of Pinot Noir. M. Foëx mentions it too as distinct from the varietal known in Burgundy as pinot blanc chardonnet. We have long looked for pinot blanc, which the vignerons said was cultivated at large in the vineyard of Montrachet. But this varietal only exists in accidental instances in the vineyards of the Côte. (…) It is an accident of the pinot noir, perhaps a step back, that has without a doubt been fixed for a long time, but that was not multiplied because of the rampant confusion between pinot blanc and chardonnet.

“Chardonnet: Chardonnet is a plant specific to Burgundy; it has been cultivated there for a very long time; it is this plant which constitutes the great white wine vineyards of Meursault, Chassagne-Montrachet. It is by mistake that one calls it pinot blanc chardonnet, noirien blanc, because it is not a pinot blanc.”