Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru Clos Saint-Jacques

At a Glance

- Size: 1.00 ha (2.47 ac)

- Variety: Pinot Noir

- Vine Age: Half planted in 1957, the other half in 1972

- Terroir: East/southeast-facing, 315m average altitude, shallow brown limestone soils.

- Viticulture: Sustainable, organic practices

- Vinification: 30-50% whole cluster, ambient yeast fermentation in open wood vats with punch-downs. Aged 18-20 months in barrels (approx. 35% new). Short blending period in tank before bottling.

Additional Info

Etymology:

Saint Jacques: Saint James in English, specifically Saint James The Great, son of Zebedee, and one of the twelve apostles. This area is known as La Côte Saint-Jacques (not to be confused with the AOC in the Chablis area.) Tradition has it that the name was given to the area a long time ago, after a stone statue of Saint Jacques was found in the Clos Saint-Jacques. It was also a resting place on one of the numerous paths of the Camino de Santiago, the famous pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint James in Galicia. The pilgrimage is known in French as pélerinage de Saint-Jacques de Compostelle.

Site description:

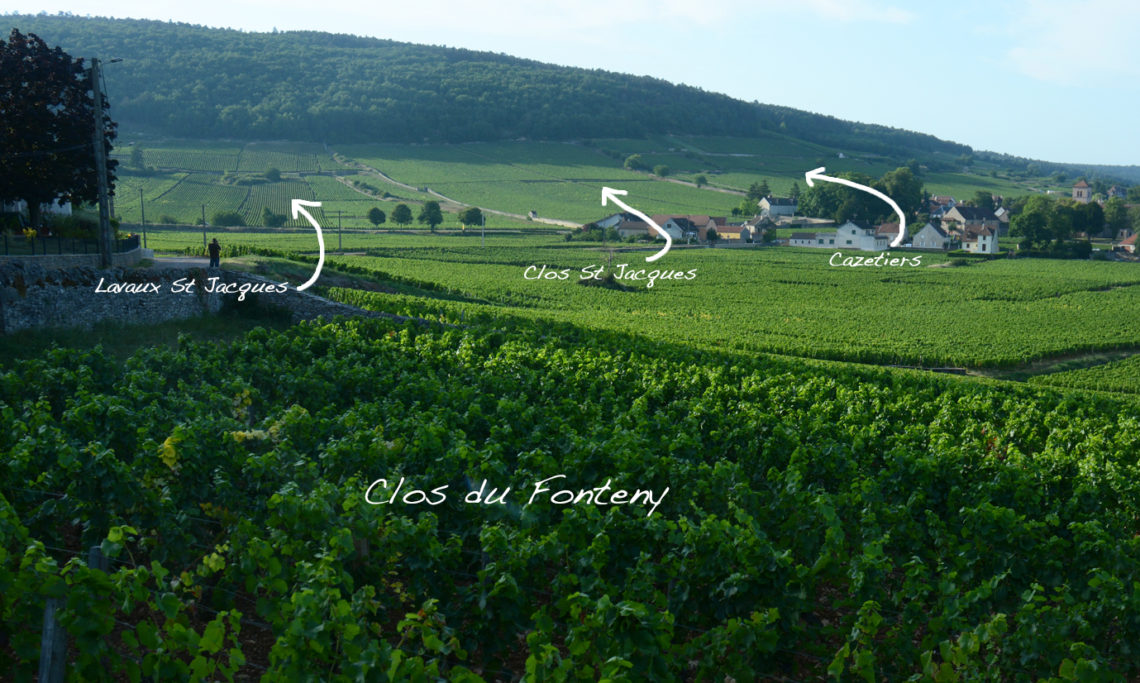

Le Clos Saint-Jacques is a 6.7 ha vineyard located at the mouth of the Combe de Lavaut, where the hill turns from a more southern to a more eastern exposure. It faces south southeast.

It is a steep slope on Burgundian standards, with an overall 17% slope gradient that is steeper towards the top and more gradual as it flattens out towards the bottom in classic, concave Burgundian fashion. It is at an elevation of 290 to 345 meters. This is quite high for a first rate vineyard: 40 meters higher at the top than Clos de Beze, and 20 meters higher than Vosne-Romanée les Reignots, for example.)

Le Clos Saint Jacques is an exceptional premier cru, so much so that many people think it ought to be a grand cru. One story states that the only reason it is not a grand cru is because of an administrative oversight. (See below.)

However, if Clos Saint Jacques does rival some of Gevrey-Chambertin’s grands crus, it does not rival the two best at their best. And we think that if you asked the Clos Saint Jacques for its opinion on the matter, it would tell you that it prefers to be the best of its class rather than not the best of the class above. Clos Saint Jacques needs no hyperbole. Its calling is noble enough.

That being said, there are vintages in the Clair cellar when both Clos de Beze and Clos Saint Jacques are at their best, yet when we prefer Clos Saint Jacques for its redder, fresher fruit. But we would not claim that it is greater. One must strive to separate personal preference from hierarchy.

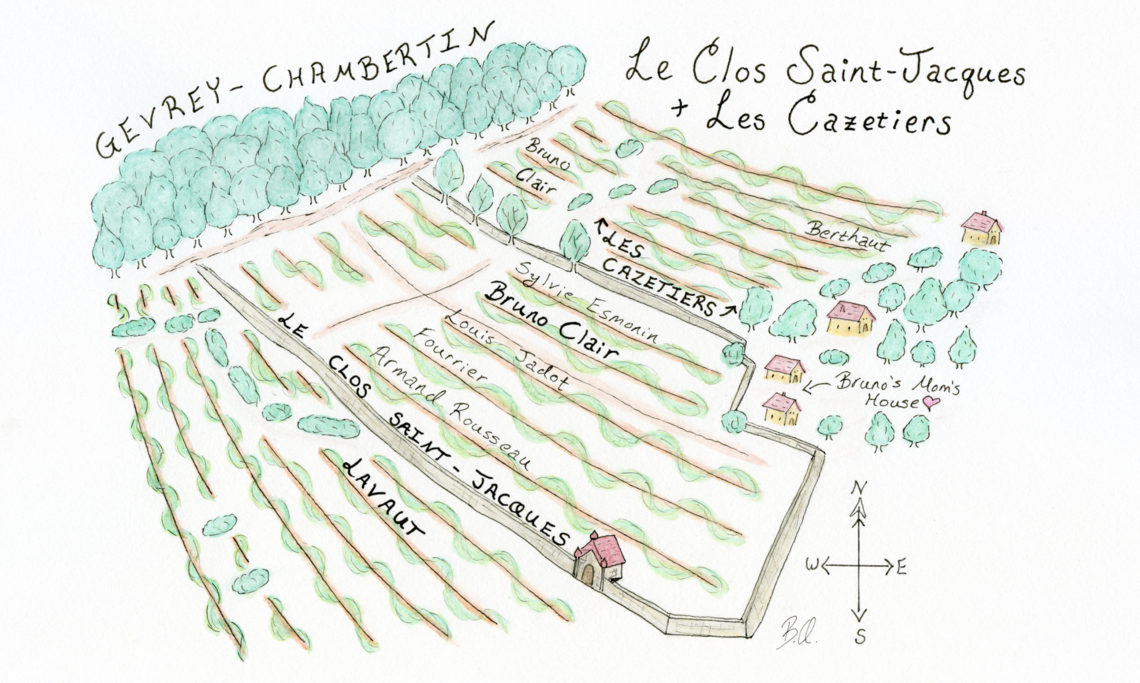

A part from being an exceptional terroir, there is a reason for the consistency of the vineyard. At the time of its sale in 1954, it was divided in strips running the full elevation, with the four new proprietors (Rousseau, Fourrier, Clair-Dau, and Esmonin) each obtaining a complete slice of the terroir. In 1985, Domaine Clair-Dau was split up, and half of their Clos Saint Jacques was sold to Jadot.

Not all of the current Clos-Saint-Jacques was part of the original clos. According to Charlotte Fromont, “In 1828, there are two distinct lieux-dits. The Saint-Jacques lieu-dit occupies the upper third of the hillside (2 ha 59 ares 15 ca.) It is divided in 18 parcels for 10 proprietors. The bottom part, or two-thirds of today’s Clos-Saint-Jacques, is one single clos and part of the lieu-dit Le Village (…). However, this clos (3 ha 82 ares 80 ca in 1828) is shortly thereafter known as Clos-Saint-Jacques.” In 1855, Lavalle mentions both Saint-Jacques and Clos-Saint-Jacques, but lists them together as a premiere cuvée, with a total area of 6.52 ha. In 1920, Rodier only mentions the upper part only, Saint-Jacques, with a surface of 2.6 ha. By the 1940s, only Clos Saint Jacques was mentioned for the entire vineyard.

Soil:

The soils of Clos Saint-Jacques are dark brown at the bottom and light brown at the top, but it is not the cement-like terres blanches that are found at the top of Les Cazetiers. The soils are clay-rich and increase in depth significantly from the top of the slope (15 cm) to the bottom (over 30 cm). Below the topsoil is a thick layer of laves, and then more soil before reaching the limestone bedrock. Bruno believes that this unique layer of laves allows the heavy clay soils to drain well.

The soils here are very rocky, with up to 45% gravels and cobbles, most of which are angular, indicating erosion from upslope. However, the presence of the “Gevrey silex” and a significant proportion (5-10%) of rounded cobbles, indicates a more significant alluvial component in Le Clos Saint Jacques than in Les Cazetiers. This is not surprising, considering its proximity to the massive Combe de Lavaut.

Bedrock:

The upper half of the vineyard, from top to bottom, consists of a thin band of the ostrea acuminata marl, followed by a large band the fossiliferous Crinoidal limestone, and then a faulted section of the hard, pink Premeaux limestone.

The bottom half of the vineyard consist mostly of hydraulic limestones, except for a little triangle in the southeast corner where there is Premeaux limestone again.

The Clair parcel:

It is 1 ha today, but prior to the 1985 sale to Jadot, it was twice the size. The vines were planted half in 1957 and half in 1972. Bruno has 25 rows. As a reminder the owners, from south to north are: Rousseau, Fourrier, Jadot, Clair, and Esmonin.

To be or not to be grand cru

“The story goes”, writes Jasper Morris, “that at the time of the [1930s] classification the Clos was entirely owned by the snobbish Comte de Moucheron, who did not deign to fill in the forms necessary to apply for grand cru (or indeed any other) category.”

[Rousseau’s website puts it this way: “this fervent royalist did not want to introduce his wine in a republican system of classification of plots.”]

“He also alienated the tribunal by sneering at such bodies and lighting up a cigarette,” Jasper continues, “which he was then obliged to smoke outside while the deliberations took place, according to Louis Trapet who was present. Nobody else was going to propose grand cru status on his behalf, so premier cru it became.”

The vineyard was sold in 1954 to Rousseau, Fourrier, Clair-Daü, and Esmonin. Rousseau says that at the time of the sale the bottom portion of the Clos Saint Jacques was planted to alfafa.

With many thanks to geologist Brenna Quigley for putting the physical and geologic aspects of these vineyards into words far more meaningful than we could have written on our own.www.brennaquigley.com

We are also indebted to geologist Françoise Vannier of Adama Terroirs Viticoles, who created the bedrock map for Gevrey that Brenna based part her work on. www.adama-terroirs.fr

Wines

-

White

-

Rosé

-

Red

- Aloxe-Corton

- Chambolle-Musigny Les Véroilles

- Chambolle-Musigny 1er Cru Les Charmes

- Fixin Champs Perdrix

- Gevrey-Chambertin

- Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru Clos du Fonteny Monopole

- Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru Petite Chapelle

- Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru Les Cazetiers

- Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru Clos Saint-Jacques

- Marsannay Rouge

- Marsannay Les Vaudenelles

- Marsannay La Charme Aux Prêtres

- Marsannay Les Grasses Têtes

- Marsannay Les Longeroies

- Morey-Saint-Denis En La Rue De Vergy

- Savigny-les-Beaune 1er Cru Les Jarrons

- Savigny-les-Beaune 1er Cru La Dominode

- Vosne-Romanée Les Champs Perdrix

- Vosne-Romanée 1er Cru Aux Raignots

- Bonnes-Mares Grand Cru

- Chambertin Clos de Bèze Grand Cru